THE MANIFESTO

Many people have not read the words of Jesus. The easy recourse is to blame them for their carelessness; the harder task is to turn his script into the unwritten prose of our daily lives.

One of the rituals of democracy is the publication of the party manifesto, setting out vision and goals. Hardly anyone reads a manifesto from cover to cover, if they open it at all. This is partly because the media can summarise each manifesto quickly and without the pain of personal research. It is also because we expect the authors to put a shiny gloss on the painstaking and compromised reality of governing. When campaigning, presentation is more important than substance. We endlessly complain about this, but are not willing to admit how much appearance matters in the judgments we make of people and their institutions.

Manifestos have also become more guarded, promising mere incremental change in the spheres governments still control in a globalised economy. This has become more apparent in the current downturn. We have moved from ideology to managerialism; the underlying question being who can preside over the system most effectively. After the polarisation of the 1980s, more people are suspicious of big ideas and revolutionary change.

There are at least three components to a manifesto:

Draw on the traditions of your political party. The general public may not read your manifesto, but the party workers will and they are looking for connections to the past, when they joined up with passion in the first place. All political parties should draw on their roots to renew their vitality.

Don’t promise something you can’t deliver. If you do, it may come back to haunt you. George HW Bush is often held up as a warning here. His promise in 1988 not to raise taxes was broken when the budget deficit compelled him to. It may have been a responsible, pragmatic step to take, but it lost him the next election to Bill Clinton. Nick Clegg’s promises over tuition fees have come in for similar contemporary treatment.

Make your promises for the long term. There are few immediate solutions in politics and it helps to be able to come back to the electorate saying your job is simply unfinished. Barack Obama clearly benefited from this tactic as might other democratically elected governments during the global downturn.

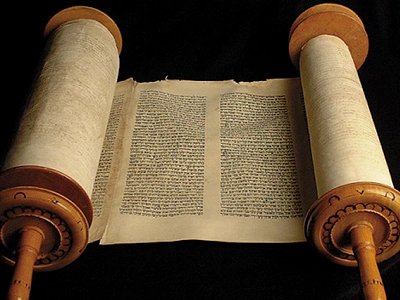

In Luke 4 there is another manifesto: the public platform of Jesus of Nazareth. Soon after the start of his ministry, there was a surge of interest, based on his teaching and spread by word of mouth in the region. His emergent charisma was clear on the day he visited the synagogue in the place he was brought up. The scroll of the prophet Isaiah was handed to him and he takes a moment to seek out a specific piece of scripture:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.

Most of us have at some point known that every eye is focussed on us to the exclusion of all others. It can be an uncomfortable moment, especially if people are waiting to hear what you are about to say. Sitting down, Jesus calmly and unequivocally announces his candidacy for Messiahship.

So how does he measure up to those three criteria of a successful manifesto?

Jesus drew deeply from the well of history and tradition. This manifesto is lifted from Isaiah 61 which describes the Messianic hope of Israel. He is not a break from the past but the fulfilment of a longed for future. This scripture was replete with spiritual resonance and in drawing on it, Jesus made all the right connections.

On the second criterion – not promising something you can’t deliver – Jesus took an incalculably great risk in aligning himself with Isaiah 61. He had to supply tangible results which demonstrated he was no mere mortal and this he provided in abundance with a breathtaking vocation of healings, miracles and teaching. Every generation longs for someone they can believe in and if such a person is not available, they may end up believing in a charlatan. What a privilege it was for the ancient and anonymous people of Galilee to be blessed with the emerging authority of Jesus.

The third component of a manifesto – making promises for the long term – is the one that gives us a headache. At the end of his reading, Jesus said: ‘today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing’. That sense of the moment – right here, right now – would have captivated his listeners. But what about us today?

The risk is that we become subsumed in the same kind of incremental and managerial approach to change which marks today’s political system. It would be naïve to think we can operate with the same unfettered liberty the early Christians were able to, surrounded as Anglicans are by the buildings, laws, customs and expectations which attach to an historic and established Church. But we sometimes behave as if these requirements must inhibit our primary calling, when they need not.

Nothing of what has evolved in church history should separate us from the radical manifesto proclaimed that Saturday in Galilee long ago. It is the essence of our calling and the hope of the world to come. The poor, the captive, the blind and the oppressed are to be relieved of their suffering. These are the roots that give life to the stem and we should water them regularly. Up and down the country and widely across the world churches are giving form to this poetic calling. They do not shout and draw attention to themselves, for this would undermine the service they offer; in this they differ from a political party which understandably wishes to show what it has achieved. Yet there may be an inherent danger in self-effacement: that we do not inspire one another by example.

Human beings are easily distracted and churches, in common with other bodies, can eventually lose a grip on their core purpose. For us this core is Luke 4: the call to preach the good news and demonstrate by tangible action that we mean what we believe. In an era where it feels the Church must respond to other agendas, we do well to submit any call to action to this test of liberty: will the oppressed be set free? If they are, then we are succeeding at our task.

As churches and as individual people it is our privilege to imagine ways we might enact this manifesto. It does not require great resources and can be implemented by the smallest gesture: putting an arm round a crying person; writing a note to a discouraged worker; talking to someone other people ignore. At times we respond instinctively in the spirit of this manifesto; in other moments we stumble cluelessly around the opportunities God artfully lays in our path. Our actions should be more intentional. Many people have not read this manifesto of Jesus. The easy recourse is to blame them for their carelessness. The harder road is to turn this script into the unwritten prose of daily life, for to understand what we believe, people must first observe how we live.

One party manifesto was famously described as the longest suicide note in history (you may remember, if you were voting in 1983). These words of Jesus are the shortest prescription for healing we possess. It is a manifesto to die for, and to live by.

POPULAR ARTICLES

Obama's Covert Wars

The use of drones is going to change warfare out of all recognition in the next decades.

Through A Glass Starkly

Images of traumatic incidents caught on mobile phone can be put to remarkable effect.

What Are British Values?

Is there a British identity and if so, what has shaped the values and institutions that form it?